The New

Zealand Tunnelling Company

In September 1915 the Imperial Government requested that New Zealand raise an Engineer

Tunnelling Company of three or four hundred men.They would form one of 25 British and seven

Dominion Tunnelling Companies, totalling 25,000 men that would serve in France by late 1916.

The officers selected for commissions in the Tunnelling Companies were often mining engineers of

wide experience, recruited from all parts of the world, largely by the efforts of the

Institution of Mining and Metallurgy, and the Institution of Mining Engineers.

Miners in New Zealand were already a brotherhood before coming together to fight overseas. A

number with Australian origins would enlist from Waihi. Men like Sapper William Pascoe, whose

Australian gold miner father lived in Waihi, enlisted in the Australian Tunnelling Corps.

In the Waihi region these men

were coming from what was one of the foremost industrial sites in New Zealand. The region was

widely regarded for its technical innovations such as the introduction of electric power, the

development of tube mills, and the refinement of cyanide gold recovery technology.

In the Waihi region these men

were coming from what was one of the foremost industrial sites in New Zealand. The region was

widely regarded for its technical innovations such as the introduction of electric power, the

development of tube mills, and the refinement of cyanide gold recovery technology.

Many miners had strong political views. In New Zealand arguably the most well known example is

the Waihi May - November 1912 strike that divided the town. Events reached a climax with the

storming of the Miners’ Hall and the ‘Black Tuesday’ death of a striker.

left: The

Hauraki Goldfield was widely regarded for its technical innovations.

Mining communities were no strangers to loss and deprivation.

It was against this background of comradeship, innovation, self-sufficiency, strong conviction

and fierce pride that Waihi would supply the second largest group of men to enlist, with only

Auckland providing more.

Tunnelling Company enlistments were, on the average, middle aged, ranging from thirty up. A

newspaper of the day reports: ‘All were strong and hardy. These were no boys playing at

war, but mature men, hard of muscle, hand and face.’

By October 1915, the entire company was assembled on Avondale Racecourse in Auckland.

The officers were drawn chiefly from the engineering staff of the Public Works Department, with

a sprinkling of Mining Engineers. They had all worked with men from the ordinary ranks in civil

life and knew and sympathised with their outlook.

Prior to his enlistment Captain Daniel Black Waters was Professor of Mining and Metallurgy at

the University of Otago. In 1915 he was also Vice-President of the Australasian Institute of

Mining Engineers, the forerunner of the AusIMM.

It was felt at the time that as the men were “experts in the class of work for which they

were called up,” there was no need for technical training, as in learning how to dig

tunnels and use the equipment of the day.

Instead, the men were taught squad drill without arms, learning to take orders, and routine

duties. ‘Lectures were given on saluting, dress, military law, health and other

subjects’.

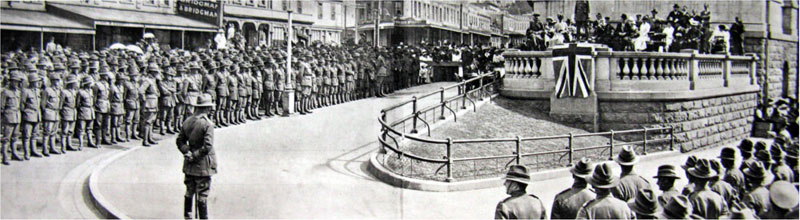

above:

Tunnelling Company enlistments on parade at Avondale Racecourse in Auckland.

The 26 November Poverty Bay Herald reported:

The Tunnelling Company, at present in camp at Avondale, Auckland, is reported to have earned

the name of the "Red Feds". There are at present in camp with this company eleven

members who were formerly secretaries of various trade unions, whilst there are over forty

who are erstwhile members of trade union committees. Most of the men in the company, are

miners who have learned their business in a hard school, and are very efficient in their own

special line. They have learned to fight their own battles.

There were to be a number of conflicts between the tunnellers and civilian authorities, many

writers describing the company as shaking up the near-by city of Auckland as it had never been

shaken before.

above:

Farewell for the New Zealand Tunnelling Company in Auckland.

The New Zealand Tunnelling Corps of Engineers left Avondale on 18 December 1915. It was noted

that, ‘the only enthusiasm the citizens of Auckland showed to the company was when they

bade it farewell’.

The Company disembarked at Plymouth and entrained for Falmouth, Cornwall where they received

training from British instructors.

It was reported that ‘Such men did not take kindly to drill and were later famed throughout

the Expeditionary force as being the toughest and roughest Company’.

The Main Body reached the Western Front in March 1916. They were the first New Zealand

Expeditionary Force men on the Western front.

No Geological establishment ever existed in the British army. Among the headquarters staff of

the Australian Mining Corps which would arrive after the New Zealanders was Major T. W.

Edgeworth David, a distinguished Professor of Geology from Sydney University who was associated

with the foundation of the Australian Tunnellers Corps.

Despite his uniform and military title, he was known as “The Professor” and would act

as geological advisor. A complete knowledge of the geology of the area was essential,

particularly the water level, for in some parts of the chalk country the miners would encounter,

the difference between summer and winter water levels varied as much as 30 feet. Initially deep

level galleries were temporarily lost by both sides due to this lack of knowledge.

There were miners in other companies too. When the New Zealand Rifle Brigade arrived on the

Western Front, men with mining backgrounds were attached to assist the work of the Australian

Tunnelling Companies. On one occasion, the New Zealand miners were detailed for the sinking of

the "Anzac Shaft," with its series of galleries, in trench 74 of the Armentieres

sector. This was the first satisfactory steel-lined water-tight shaft ever sunk in the Second

Army area; and the whole of the work was executed by New Zealanders.

The New Zealand Tunnelling Company first operated at the foot of Vimy Ridge near Arras, in a

counter-mining role. The underground war was a deadly affair, which hinged on the speed of the

digging. Tunnellers would dig a long shaft under the enemy trench system and carve out a bigger

cave at the end of the tunnel.

They would then pack the end cave with about 3000 pounds of explosives, retreat and detonate

it.

When an explosion of this size went off underground, everyone in nearby tunnels, even

unconnected to the explosion, was killed by carbon monoxide created by the blast.

As they dug, the tunnellers would listen to the digging sounds of the enemy. When digging

stopped and you could hear the enemy packing explosives you knew that if you weren't ready to

blow, you’d lost the race.

The New Zealand tunnellers dug at three times the rate of the German tunnellers and won the race

virtually every time. Only once during the war did the enemy blow a mine before the Kiwis were

able to counter-mine.

In the early days New Zealand Tunnellers knew nothing of geophone listening and they had to

learn mine rescue work and other details of mining practice as they went. Teams were sent for

training and it was a fast learning curve.

left: Geophone

listening device used by tunnellers to listen for enemy activity underground.

The tunnellers were transferred to Arras, staying there for the next two years.

It was at Arras that the New Zealanders abandoned the Royal Engineers’ method of tunnel,

switching to a more “Kiwi version” -- a typical New Zealand gallery, would be 6 feet

high by 3 feet 6 inches wide – wider and higher than the tunnels the British were used to

constructing – for “decent room to swing a pick.” They were big men and dug big

tunnels. And because they liked to see the ground they were working in – arguing that it

talks to miners who know the language – the tunnels were unlined and only supported here

and there by rough props.

The New Zealanders’ methods also differed one other respect. The British sank a vertical

shaft in a position as far forward as possible. These were vulnerable to enemy bombardment and

raiding parties. The handling of spoil was a slow and laborious task and dumping the spoil at

the surface often gave away the position of the shaft. The Kiwis preferred to commence

operations a little further back where they could conceal the mine entrance more readily and

better conceal the spoil above ground. A decline was driven to a point where a main lateral

gallery ran below the front trench line.

The company also had the job of disposing of damaged ammunition. In one incident 13,000 shells

were lowered 95 feet below the surface and stacked in one of the old mine galleries. 45 electric

detonators were prepared for an explosion.

Quite a crowd gathered to watch. When the exploder handle was shoved home, a huge column of

smoke and debris rose high in the air and slowly drifted leeward. It was reported that troops

four miles away “stood to” for a gas attack. The explosion also left a smoking

seventy-foot crater.

In Arras, the New Zealanders were credited with the discovery of old underground quarries,

limestone caverns that been excavated to provide material to rebuild the city of Arras in the

seventeenth century.

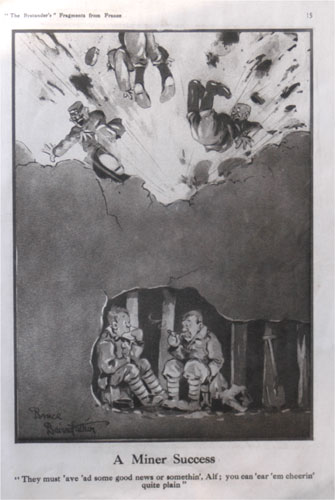

right: A

cartoon of the day. 'They must 'ave 'ad some good news or somethin', Alf;you can 'ear 'em

cheerin' quite plain'.

With a major Allied push planned for April 1917, the New Zealanders worked in the Ronville

system. They found immense caverns hundreds of feet in diameter and twenty to forty feet high.

Work began to connect and open up the underground quarries to make the system suitable to house

troops, so that when the day for the attack came the men would emerge from them safe, warm and

dry – and unsuspected by the enemy.

The chalk stone was white, resembling the Oamaru stone of New Zealand, only finer and denser in

structure, and capable of being more finely carved. The cavern system was mined in much the same

manner as a coal seam, with pillars of stone being left to support the ground overhead.

As soon as the caverns were opened to the cold wet winter air, the chalk began to swell and

crack, and slabs weighing many tons would come crashing down without warning. To timber up to

the heights of the high roofs in the Ronville caves was out of the question, so instead the

floor was raising by dumping the chalk cut from the galleries and dugouts until the roof was

close enough for clear observation and support.

For two months they were assisted by the New Zealand Pioneer Battalion, many of whose members

had been part of the Native (Maori) Contingent. Members of the NZ Infantry would replace the

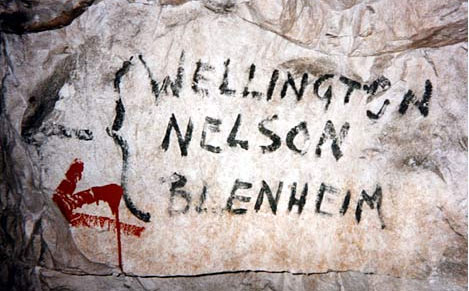

Pioneers. Today you can still see names etched on the walls.

To assist orientation New Zealanders gave the caverns along their line names from home: Russell,

Auckland, New Plymouth, Wellington, Nelson, Blenheim, Christchurch, Dunedin and Bluff.

below:

Familiar names were painted and carved into the chalk.

The caves were fitted with gas

doors, electricity, ventilating plant, running water and other facilities including a hospital

and operating theatre. Ventilation was good, the only difficulty being gas attacks, when plenty

of ventilation actually increased the danger.

The caves were fitted with gas

doors, electricity, ventilating plant, running water and other facilities including a hospital

and operating theatre. Ventilation was good, the only difficulty being gas attacks, when plenty

of ventilation actually increased the danger.

As they tunnelled towards the enemy lines three mines were laid under German trenches for

detonation when the attack began.

The cavern system was reputed to be large enough to hold between 20,000 and 25,000 men, although

during the cold winter months of the campaign known as the Battle of Arras, only half would

actually be in residence at any one time. It is thought that up to 30,000 men slept one or more

nights in the caves and many more passed through them. The development of underground shelter

for attacking troops to the extent carried out at Arras by the New Zealand Tunnelling Company is

believed to be unique in military history.

The highly secret job finished in time for the 9 April 1917 assault. the Company’s skill

and effort were such that they were mentioned in Parliament in New Zealand.

Don’t think that the Tunneling Company had an easy job. One account details their

experiences.

Leading up to zero hour Tunnelling Companies duties included repairing the constantly crumped

forward saps. The night before the assault the tunnel face was well under the German wire and

just 25 yards from the parapet of the German front line trench. A prepared machine gun lay in

position behind a couple of feet of cover that the tunnellers were to remove just before Zero

and to open the end of the gallery into No-man’s land, continuing it as an open trench into

the German front line, immediately the battle opened.

Unfortunately a ‘friendly’ shell fell short, landed in the gallery with gas filling

the space. A hastily rigged gas curtain was rigged behind the first opening – an incline up

to the front trench. The end had to be opened up to clear the gas out. This meant groping by dim

candle light, through a hundred and fifty yards of narrow winding gallery with eyes streaming

and smarting from the tear gas that got in under the box respirators. Constant relays of men

were necessary before the work was done.

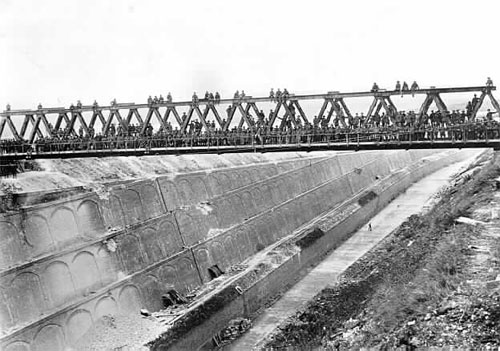

The next big task given to the

New Zealand Tunnellers was the construction of the Havrincourt Bridge over the Canal du Nord. It

was to be a notable engineering feat. The men were not a trained bridging company and had little

equipment for the task. Up to the morning of the attack the canal was practically front line so

no preliminary work could be done beyond taking measurements. The type of bridge to be erected

was the pre fabricated steel “Hopkins’, designed to carry heavy loads across a clear

span between supports of 120 feet. The canal was at that point through a cutting 85 feet deep

and with a distance of 180 feet.

The next big task given to the

New Zealand Tunnellers was the construction of the Havrincourt Bridge over the Canal du Nord. It

was to be a notable engineering feat. The men were not a trained bridging company and had little

equipment for the task. Up to the morning of the attack the canal was practically front line so

no preliminary work could be done beyond taking measurements. The type of bridge to be erected

was the pre fabricated steel “Hopkins’, designed to carry heavy loads across a clear

span between supports of 120 feet. The canal was at that point through a cutting 85 feet deep

and with a distance of 180 feet.

left: The

Havrincourt Bridge

From an engineering point of view the task set Captain J.D. Holmes acting O.C Company, verged on

the impossible.

Eight days from start, the bridge was finished, complete with footways and handrails. It was

reputed to have been the longest single span military bridge up to that time. Captain Holmes was

the son of R W Holmes, the public works engineer who was responsible for another remarkable

engineering feat, on the North Island railway known as the Raurimu Spiral.

As the war finished, a legacy of ‘miners at war’ stories includes;

Professor D B Waters of Otago University, one time manager and general manager of mining

companies in both Australia and New Zealand and for a brief time while serving overseas, OC of

the NZ Tunnelling Company would return home but with his health was damaged by war service.

Waihi’s Lance-Corporal Jack

Norris was awarded a DCM His citation reads; “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to

duty. He displayed the great coolness and courage when he and his party were entombed in a

gallery. There was a great risk of the workings being discovered, but he succeeded in getting

his party dug out undetected.”

Waihi’s Lance-Corporal Jack

Norris was awarded a DCM His citation reads; “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to

duty. He displayed the great coolness and courage when he and his party were entombed in a

gallery. There was a great risk of the workings being discovered, but he succeeded in getting

his party dug out undetected.”

Norris displayed qualities miners were known for. They would readily sacrifice their lives to

save their workmates.

right: Lance

Corporal Jack Norris is buried in Waihi.

An unveiling ceremony of the War Memorial of the Institution of Mining and Metallurgy was held

in London in 1921.

Attending was Field –Marshall Earl Haig, senior commander of the World War One British

Expeditionary Force. In his address he said, ‘You have afforded me an opportunity to say

a few words of special thanks for a body of men in France that seldom drew upon itself much

notice or glory at the time, but was surpassed by none in the demands it made upon the

skill, the courage and the resolution of the individuals concerned, or in the services it

rendered to the Army as a whole.

Few outside of those who took part in the work and benefited by its results realise the

immense amount of steady, persistent toil in every circumstance of peril, surrounded by

danger in a form that might appall the stoutest hearted, that went to the preparation of

triumph. Few realise how vast, how important to the safety, comfort, and success of our

troops, was the work of the miners, work that was little commented upon in the Press, but

yet went steadily and continuously, day after day, and year after year, along the whole of

the British Front.’

Until recently, few people have known about the stories of the special group men who fought an

underground war or of the men from the Hauraki goldfields from places like Waihi, Karangahake,

Thames and Waitekauri.

They left from the mines to work in secret, underground in France. They worked in extreme work

and weather conditions. They were buried underground, gassed and shelled. At their own special

work, mine warfare, they showed the highest qualities both as military engineers as well as

fighting troops.

.

They returned to New Zealand, to Waihi and their jobs. In their home country, they were

forgotten.

We would like to remedy that. As we head towards the centennial commemorations of World War One

there are plans to erect a Memorial to New Zealand Tunnellers in Waihi.

(Extracts from ANZAC Day presentation, 2008)

Miners at War

written for Quarrying & Mining magazine

On the Western Front

Personal accounts and newspaper reports

News from the Other Side of the World

Letters home (PDF)

A Tunneller's grandson tells his story

Committee member Mike Roycroft tells the story of his grandfather

The Caves of Arras

Thames Star 1917

Good War Service

Evening Post 1919

Most Frightful Fight Ever Seen

Wanganui Chronicle 1917

The New Zealand Tunnelling Company

J.C.Neill, 1922

Waihi Tunnellers

Maori Television 2010

Unit

War Diary, Arras

Nov 1916-April 1917

It was felt at the time that as the men were 'experts in the class of work for which they were called up', there was no need for technical training, as in learning how to dig tunnels and use the equipment of the day.

...many writers described the company as shaking up the near-by city of Auckland as it had never been shaken before.

‘the only enthusiasm the citizens of Auckland showed to the company was when they bade it farewell’.

The underground war was a deadly affair, which hinged on the speed of the digging.

To assist orientation New Zealanders gave the caverns along their line names from home: Russell, Auckland, New Plymouth, Wellington, Nelson, Blenheim, Christchurch, Dunedin and Bluff.